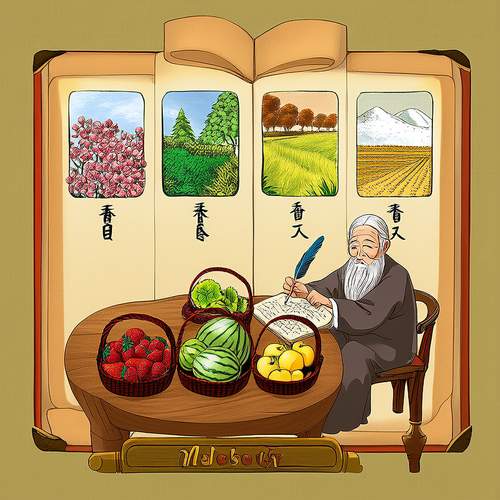

The ancient wisdom of eating with the seasons has been practiced across cultures for millennia, yet in our modern world of globalized food systems, we've largely lost touch with nature's dietary rhythms. Seasonal eating isn't just some romantic notion from the past - it's a scientifically supported approach to nutrition that aligns our bodies with the earth's natural cycles. As each season brings its unique environmental conditions, our nutritional needs subtly shift in response to temperature changes, daylight hours, and atmospheric conditions.

Spring's Reawakening

When winter's grip loosens and the first tender greens push through the thawing soil, our bodies instinctively crave lighter fare after months of hearty comfort foods. This is no coincidence - the bitter greens like dandelion, arugula, and mustard that emerge first in spring contain compounds that support liver function, helping our bodies detoxify after winter's heavier eating patterns. Traditional Chinese medicine has long recognized spring as the season of the liver and gallbladder, recommending sour flavors like lemon and vinegar to stimulate bile production.

The appearance of spring onions, garlic scapes, and ramps in early spring isn't just a culinary delight - these allium family vegetables contain sulfur compounds that boost immunity as we transition from indoor to outdoor living. Asparagus, that quintessential spring vegetable, acts as a natural diuretic, helping reduce water retention from winter's saltier foods. Even the short-lived appearance of morel mushrooms in spring serves a purpose - their unique polysaccharides may help modulate spring allergies by supporting immune regulation.

Summer's Abundant Vitality

As temperatures rise and daylight stretches long into evening, nature provides cooling, water-rich foods to help us stay hydrated and balanced. Juicy tomatoes, crisp cucumbers, and succulent melons all contain over 90% water while providing essential electrolytes lost through summer perspiration. The bright reds and oranges of summer fruits like peaches, nectarines, and berries aren't just visually appealing - these colors signal high levels of carotenoids and flavonoids that protect our skin from increased sun exposure.

Interestingly, many traditional cultures consume spicy foods in hot weather - think of Thai cuisine or Mexican salsas. This isn't just about bold flavors. Capsaicin in chili peppers actually helps regulate body temperature by inducing sweating, while antimicrobial compounds in spices like turmeric and cumin protect against foodborne illnesses that increase in warm weather. The light, raw salads and ceviches popular in summer make perfect sense from a nutritional standpoint - they're easier to digest when blood flow is directed toward skin surfaces for cooling rather than deep digestion.

Autumn's Harvest Wisdom

As days shorten and nights grow crisp, nature provides the perfect transition foods to prepare our bodies for winter. The earthy squashes, sweet potatoes, and root vegetables that dominate fall harvests are rich in complex carbohydrates and beta-carotene, which converts to vitamin A to support mucous membrane health as indoor heating season begins. Apples and pears, with their soluble fiber pectin, help regulate blood sugar swings that can occur with decreasing daylight.

Autumn is also mushroom season, and these fungal wonders provide immune-modulating beta-glucans perfectly timed for cold and flu season. Traditional Chinese medicine recommends slightly warming foods in fall - think roasted rather than raw - to begin building internal warmth. This is when nuts reach their peak, offering healthy fats and minerals to support nervous system function as we adjust to less sunlight. The deep reds and purples of fall grapes and berries provide anthocyanins that support circulation as temperatures drop.

Winter's Deep Nourishment

When the natural world rests in winter, traditional diets worldwide emphasize hearty, nutrient-dense foods that provide sustained energy and warmth. Bone broths, a staple in winter traditions from Korean seolleongtang to Jewish chicken soup, provide easily absorbed minerals and gelatin to support joints that often stiffen in cold weather. The brassica family - kale, Brussels sprouts, cabbage - shines in winter, providing sulfur compounds that support detoxification when we're exposed to indoor pollutants and less fresh air.

Winter is the season for healthy fats in traditional diets - from the olive oil of Mediterranean winters to the seal fat consumed by Arctic peoples. These fats provide concentrated energy and help maintain cell membrane flexibility in cold temperatures. Citrus fruits arriving in winter provide not just vitamin C but also bioflavonoids that strengthen capillaries against winter's dry air and temperature fluctuations. Even the timing of winter spices makes sense - cinnamon, cloves, and nutmeg all contain compounds that mildly raise body temperature while supporting digestion of heavier winter fare.

The Forgotten Fifth Season

Many traditional systems, including Ayurveda and Traditional Chinese Medicine, recognize late summer or early fall as a distinct fifth season focused on earth elements and digestion. This is the time of abundant grains, late summer fruits, and the beginning of the harvest. Foods like millet, corn, and late berries support spleen and stomach health according to these systems. The slightly damp, transitional quality of this period calls for foods that prevent dampness accumulation in the body - think of how traditional cultures naturally lean toward fermented foods and drying preparation methods during this time.

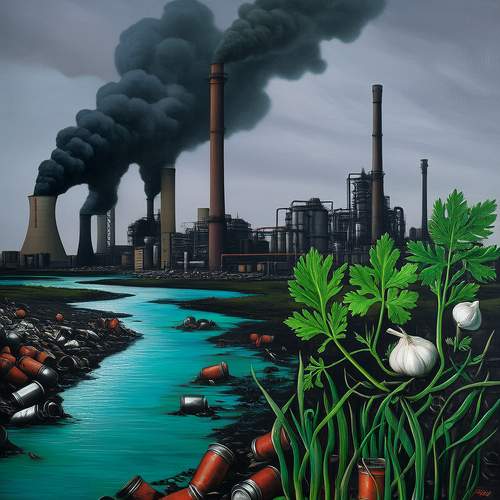

Modern Challenges to Seasonal Eating

Our global food system has severed the natural connection between what grows locally and what appears on our plates. While we can now enjoy blueberries in January or butternut squash in July, this convenience comes at a cost. Studies show that produce loses nutrients during transport and storage - spinach can lose up to 90% of its vitamin C within 24 hours of harvest when not properly stored. Furthermore, eating the same foods year-round may contribute to developing food sensitivities, as our ancestors naturally rotated foods with availability.

The environmental impact of out-of-season eating is staggering. A 2021 study calculated that importing off-season produce generates up to 10 times more carbon emissions than eating seasonally and locally. There's also growing evidence that our gut microbiomes may benefit from seasonal variation in fiber sources, just as they did for our ancestors who ate dramatically different diets throughout the year.

Practical Steps Toward Seasonal Eating

Transitioning to seasonal eating doesn't require perfection. Start by learning what's in season in your region - many agricultural extensions publish seasonal produce calendars. Visit farmers markets where the offerings naturally reflect seasonal availability. When shopping at supermarkets, look for country-of-origin labels and choose produce from the closest location possible. Consider preserving seasonal abundance through freezing, drying, or fermenting to enjoy summer's bounty in winter months.

Notice how your cravings naturally change with the seasons - that desire for hearty stews when the first chill arrives or crisp salads when summer heat peaks is your body's innate wisdom speaking. By realigning our eating patterns with nature's cycles, we not only nourish ourselves more effectively but also participate in the ancient rhythm of life that sustained our ancestors for generations untold.

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By Michael Brown/May 18, 2025

By James Moore/May 18, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/May 18, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/May 18, 2025

By James Moore/May 18, 2025

By Laura Wilson/May 18, 2025

By Emily Johnson/May 18, 2025

By Joshua Howard/May 18, 2025

By David Anderson/May 18, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/May 18, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 22, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Apr 22, 2025